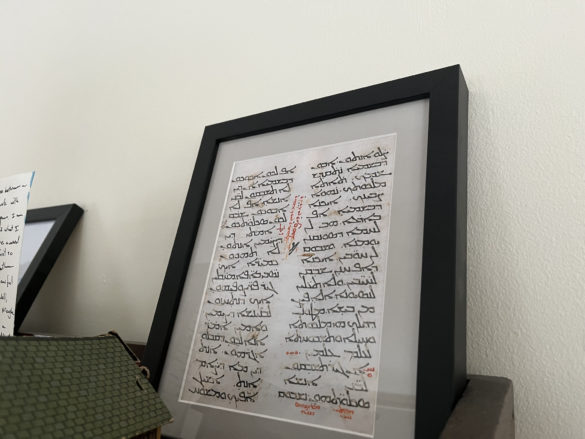

If you ever stop by my office, you’ll see a framed document sitting on top of my bookshelf that you’re probably not able to read. If you’re familiar with Arabic writing, it may seem familiar; but it’s not quite the same. It is, in fact, Aramaic, not Arabic; the language of Jesus, not of the Quran. And the text is the text of the Lord’s Prayer in an ancient manuscript of the Gospel of Matthew written in Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic—the closest thing we have, in a sense, to the original words of the prayer Jesus taught his disciples.

There are no hidden secrets or bombshell revelations in the Aramaic text of the Lord’s Prayer. The text that sometimes circulates online as a translation of the “original Aramaic text” is, unsurprisingly, a very modern creation. But to me, this text is more exciting than any Da Vinci Code invention could be. It’s a tangible connection to an ancient and living tradition, that stretches back through two thousand years, still speaking a dialect of a language quite similar to Jesus’ own.

Our stories about the history of Christianity often focus on its westward spread, from its origins in Jerusalem through Paul’s journeys around the cities of ancient Greece to Peter’s martyrdom in Rome; the Church’s domination of medieval Europe and its early-modern colonization of the world. But at the same time Christianity was spreading west, it was also spreading East. And in fact, by the 600s AD — at the same time many German and Anglo-Saxon tribes were being reluctantly converted to Christianity, well before the conversion of Scandinavians, Russians, or Poles, Christian missionaries had begun spreading the good news as far as China.

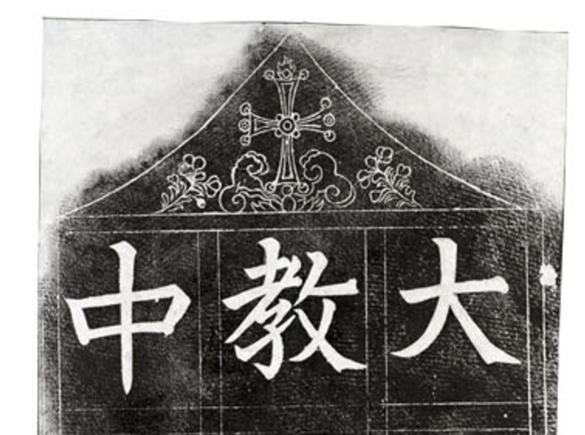

These missionaries mainly came from the tradition that’s known as the “Church of the East.” Centered in what are now Syria, Iraq, and Iran, these churches spread east along the Silk Road toward China and south into India, thriving especially among merchant and migrant communities of Persians. By the 8th century Christianity had a long enough history in China that in the year 781, a memorial was created in Xian to celebrate its 150th anniversary in the country, mixing writing in Chinese characters with Syriac text and images of the cross.

If you’ve never heard of this tradition, it’s no surprise. It’s been subject to persecution over and over again for nearly 1500 years. The Church of the East has always lived as a minority, wherever it was: first as Christian refugees fleeing across the border into Persia from Roman oppression, then as a Christian minority within a Zoroastrian and later Muslim society. Christians were expelled from China in the 9th century, never to return; minority Christian communities in central Asia experienced alternating periods of discrimination and outright persecution under different local leaders. The Syriac Christian heartland of northern Iraq has seen recurring periods of violence in the modern era, including the Assyrian Genocide that occurred alongside the Armenian Genocide, and more recent violence by ISIS and other radical forces in the region, such that the predominant centers of the Syriac tradition are now among expatriate and refugee communities of Assyrians in Sweden and the United States, and the Grand Catholicos of Seleucia-Ctesiphon and Patriarch of the Church of the East has his seat at Mar Gewargis Cathedral in… Chicago.

There is no hidden mystical meaning to the Aramaic words of the Lord’s Prayer. But there is much to be learned from the Assyrian tradition that has carried them on. I wonder in particular about what lessons we can learn, as our church loses the power it once had, about what it means to be a small religious community embedded within a larger society. What does it mean to spread the good news without social and political power? What does it mean to live as faithful Christians, when the society around you doesn’t particularly care? What does it mean to transmit the traditions of your faith, generation after generation, as your numbers slowly dwindle and it seems your church may die?

There are no easy answers, but there is, at least a model—living evidence that Christianity can survive and even thrive outside the structures of Christendom that prop it up.