The feast of the Epiphany celebrates the manifestation of Christ to the Gentiles, the moment in which the God of the Jewish people was revealed to all the peoples of the world. Many of us are accustomed to thinking of Christianity as a primarily European religion—a faith concentrated in Europe and spread around the world by European colonization and imperialism. But in reality, some of the oldest Christian communities in the world are found in parts of Africa and Asia, and their living traditions can provide us with an interesting perspective on our own.

Our Thursday discussion series this winter will take up this theme, learning about and from ancient and modern Christian traditions from around the world. But I know that many of you can’t be there, so I thought I’d offer short versions of some of those presentations on Christian traditions from around the world in textual form, instead!

This week, I’ll say a few words about the Coptic Christian tradition of Egypt.

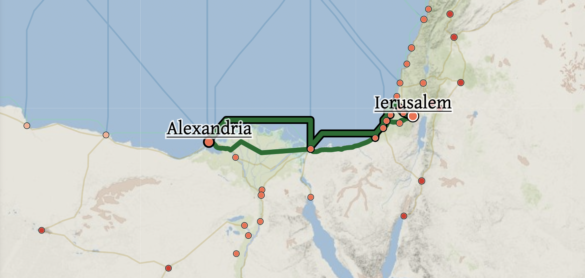

Egypt was one of the centers of the ancient Jewish community, and of early Christianity. The great city of Alexandria lay just a week’s journey by donkey and boat from Jerusalem, a journey roughly equivalent to the distance between Boston and Washington, DC. Alexandria was a major metropolis, a center of learning and Greek culture, and a hub for the Jewish diaspora in the Mediterranean during the period of Greek and Roman rule. As Christianity began to spread, Alexandria became one of its major intellectual centers: even before the legalization and then official adoption of Christianity in the Roman Empire, Alexandria was home to prominent Christian theologians like Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215) and Origen (c. 185-253), both affiliated with the Catechetical School of Alexandria, a kind of early Christian proto-university.

Egyptian Christianity developed into a tradition of contrasts. Its intellectual and episcopal leaders in cities like Alexandria were typically native Greek speakers, deeply formed in the Greek intellectual tradition, and learned in the literary analysis of the New Testament (written in Greek) and the Greek translation of the Old Testament, known as the Septuagint. But the overwhelming majority of Egyptians continued to speak the Egyptian language, a direction of the language of the hieroglyphs and Pharaohs. As Christianity spread, a distinctive “Coptic” tradition developed, in which Christian scribes wrote the Egyptian language in Greek letters, while borrowing many Greek philosophical and theological terms. After the Islamic conquest of Egypt several centuries later, as Arabic replaced Greek as the language of government and official religion and began to displace the Egyptian language, another bilingual tradition emerged: while even Egyptian Christians spoke Arabic in their daily lives, Coptic remained (and remains) the language of liturgy and prayer.

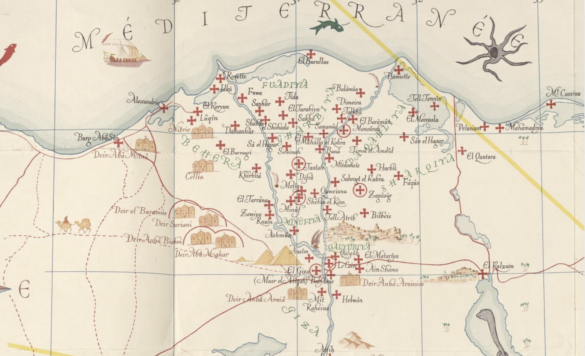

Egyptian Coptic Christianity is a tradition of contrasts in another way, as well. You can see the contrast in this 19th-century map of Egyptian Christian sites. (The red crosses on the map show parishes and dioceses; the brown buildings show monasteries.) Along the Nile River, in the fertile delta, and on the coasts, local parishes and bishoprics flourished where populations were dense. On the outskirts of Egyptian societies, monasteries grew up around the sites where the early “Desert Fathers and Mothers” had gone.

Egypt was the home of early Christian monasticism, and it’s easy to see why. Early ascetics and spiritual seekers went to the desert in droves—not into the depths of the Libyan Desert, but to the deserted outskirts of society, to the places furthest from the rivers, where it was barely possible to sustain life and few people lived.

The wilderness of the desert provided a refuge from the noise of the city and all its distractions. Just as in our own culture we imagine the wilderness to be a place of pure and simple living—however idealized that vision may be!—so too the ancients who sought wisdom turned to the wilderness to find a place where they could pray and meditate without distraction. At first, the desert fathers and mothers were simply individual “anchorites” turning to the desert to seek God. But soon, communities grew up around these leaders, unified in prayer and seeking to build new communities centered on their shared practices of faith, outside the ordinary boundaries of society. Monastic traditions spread from Egypt throughout the Christian world, and these early ascetics and monastics have provided a wealth of spiritual wisdom from which Christians around the world have continued to benefit.

Coptic Christianity has never had an easy relationship with secular authorities. Christianity in Egypt spent its first three centuries as an illegal religion under Rome, and most of the following three centuries in continual theological conflict with the opinions of the Roman emperors. After the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th century, treatment of Egyptian Christians alternated between toleration (with the addition of certain discriminatory taxes and fines) and outright persecution, official and unofficial—including, most recently, particularly violent aggression and church bombings claimed by ISIS. But while the Christian population of Egypt has dwindled over time, Christians still make up some 15-20% of the population of Egypt, 15-20 million people in all. In other words, there are more than ten times as many Coptic Christians in Egypt, a Muslim-majority country, as there are Episcopalians in the United States.

So what do we have to learn from a tradition that has always balanced multiple languages and cultures, that’s sought to maintain the traditions of the past and keep them alive for people who quite literally speak a different language? What do we have to learn from a tradition that lives in bustling cities but craves the wisdom found in the desert? What do we have to learn from a tradition that’s never held political power, that’s never been in charge of its country, but has remained faithful without imposing itself on the culture around it?

I’ll leave that as homework for you, but I suspect the answer is: we have very much to learn, in every imaginable way!